Three poets and one music critic put in for the job of editor of Quadrant in 1955. It was not yet called Quadrant. But it was to be a quarterly in the tradition of the Quarterly Review or the Edinburgh Review in the 19th century and Encounter in the 20th. It would be published by the Australian Committee for Cultural Freedom, under the chairmanship of the eminent jurist Sir John Latham, late of the High Court of Australia.

Kenneth Slessor was the best known of the applicants. In his submission he insisted that the magazine must above all be literary. It must certainly not be party-political. It must also avoid cultural cliques and the editor must be "free and untrammelled" by any committee or board.

There should be no problem finding contributors, he said. His own knowledge of contemporary Australian writers would be a help. He was not only a famous poet, he was literary editor of The Sun newspaper and served on the Commonwealth Literary Fund. In any case "magazines of the kind contemplated generate their own writers -- provided payment is on the highest possible scale". As a title of the magazine, he suggested Discovery, with its allusion to Captain Cook and his ship.

He added that he might not be able to give enough time to the magazine . But he would, he said, be happy to be co-editor with someone like John Thompson. Slessor, born in 1901, was the oldest of the applicants.

John Thompson, a few years younger (born 1907), had just published his third collection -- Thirty Poems. He had been a war correspondent in New Guinea and the Dutch East Indies and was now an ABC broadcaster. Willing to be Slessor's co-editor, he agreed with the older poet's insistence on the "full authority" of the editor, his detestation of literary cliques ("one of the evils of Australian cultural life") and the absolute priority he gave to literary as opposed to political standards: "I do not wish to have anything to do with politics."

He was, however, "profoundly interested in broad social issues" and had more to say about them than Slessor. The proposed magazine should reflect an Australia that was rapidly changing under the pressures of immigration, of a growing sense of our real isolation in Asia ("the Orient') and of some erosion of our entrenched sense of nationality. "The white man," he said "can hold this country." To succeed, our literature, our Western heritage , will remain "vital".

Thompson also thought the magazine should combat totalitarianism --" the abomination of abominations." But rather than denouncing Communists and their fellow-travellers, we should try to lure them over to our side : some of them are "quite well intentioned". In dealing with any controversial issue, he said, we should maintain a "British judicial detachment."

More broadly Thompson stressed the importance of adequate funding. In all these matters, "the costly way round may be the cheapest way home."

Roger Covell, a Brisbane music critic, aged 24 , was the youngest applicant. But he would brook no editorial nonsense. The magazine should be neither precious nor "offensively Australian". It should not be "anti-Communist" or "anti" anything. There must be no discrimination against Communist writers (although they would not be permitted to take over Australian nationalism under the guise of opposing a chi-chi cosmopolitanism). All contributors must be judged on literary merit. Perhaps making a virtue of a limitation, he said it may be best if the editor were "a personal stranger" to most of his writers.

The fourth applicant was James McAuley. In his late 30s (born 1917) he was of the right age and was exploding with ideas, faith, poetry and politics. Some 10 years earlier he had created the Ern Malley hoax -- probably the most significant hoax in literary history. He had elaborated its underlying ideas -- the high road of classical or traditional poetry -- in a series of essays and papers, including the Commonwealth Literary Fund Lectures of 1955. He had published his first book of verse, Under Aldebaran, in 1946 and was soon to publish A Vision of Ceremony. He had been received into the Roman Catholic Church. He had drafted several polemical pamphlets for the right-wing of the Australian Labor Party ( "the Groupers"). He had published some historic essays in the cause of decolonisation in New Guinea.

His was the longest submission for the magazine. It was also the most politically outspoken. Let me quote from its opening page at some length.

There is also a particular aspect, which may be expressed as follows. During the thirties and forties Australasian intellectual life became subjected to an alarming extent to the magnetic field of Communism. All sorts of people who would regard themselves as being non-Communist, and even opposed to Communism, in practice were dominated by the themes and modes of discussion proposed by the Communists, danced to the Communist tune, and had serious emotional resistances to being identified with any position or institution which was denounced by the Communists as 'reactionary'. Bodies such as writers' organizations, civil liberties organizations, and so on became Communist or semi-Communist in their real character .

The magazine which in Australia came nearest to being a general magazine of arts and ideas, Meanjin, became effectively a fellow-travelling publication in spite of the fact that a few anti-Communists like myself continued to contribute to it. Since the war, the Sydney monthly Voice, devoted principally to political comment, but with some general cultural features, has followed a confused and naïve line which merely prolongs the illusions of left-liberal and neutralist groups and is helpful to the Communists.

One reason for all this was that schools of thought genuinely independent of, and opposed to, Communist suggestion were in this country not well organized and publicly present. They lacked 'prestige', that magical aura which captures the minds of the young in advance of argument and establishes compelling fashion.

The task of any organization which is dedicated to the freeing of men's minds from the spells of Communist influence must include very close attention to this matter of prestige and fashion. Men's minds will be won only when anti-Communist positions can radiate a counter-attraction. It is true that this counter-attraction which is needed must in our case be generated only from truth, and not by unscrupulous manipulation; but generated it must be or the truth will remain ineffective.

That is where a magazine comes in: a magazine of wide scope and high quality. One which will interest an extensive range of people, one which will command respect even from the dubious, one which the general run of writers will want to be published in because they feel it to be a distinction to be accepted for its pages.

To put it another way, the magazine would or should speak for and to those ideological wanderers in that tense no-man's land that had largely formed McAuley in the 1930s. They were modernist, marxist and anti-stalinist, despised by communists and ignored by conservatives, the international flotsam and jetsam of the Age of Ideology. McAuley understood this world intimately. He had lived in it for most of his life. Quadrant would be for him a forum for exploring its intimations and its search for a way out of no-man's land and the way back to civilisation.

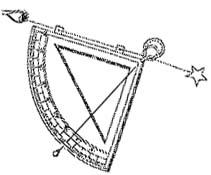

McAuley's submission also listed other objectives. The magazine should definitely be "highbrow" (in Ortega's phrase ,"at the height of our time"). It should be literary but this may be interpreted broadly: the work of Adam Smith and David Hume is literature. There should be regular "comment from the editorial chair" both on contributions or on issues at large. It should be "Australasian", that is, involve New Zealand writers. There must be no reprints from other journals. There should be lively Letters to the Editor. For its title he at first suggested "Free Market" (that is, competition of ideas), "Enquiry" or "Common Ground". Later, prompted by Alec Bolton, he suggested Quadrant, with the idea of setting a course.

The august gentlemen of the Australian Committee for Cultural Freedom, mainly lawyers and academics, and one woman (the writer Henrietta Drake-Brockman) met at the end of March 1956, in the old Albert Street wool store, to choose the editor. All the candidates were excellently qualified. But the final decision made itself.

Slessor, for all the splendours of his verse, had passed his best days. Thompson's strains also seemed to have a dying fall. Covell was, if not brash, perhaps a little young and sappy.

The only criticism offered of McAuley -- remember this is the 1950s -- was that he was a Roman Catholic, and a convert at that. For some Australians, this suggested a mindless dogmatism, a passion for censorship and a tendency to "clerical-fascism". But even the Chairman of the Australian Committee, Sir John Latham who was anti-Catholic or anti-Christian and an active Rationalist, recognised McAuley's enormous talents and strongly supported his candidature.

In the end, Arthur Denning, Director of Technical Education in NSW, nominated him for the editorship and the neurophysicist Sir John Eccles was the seconder. The editorial fee was to be 100 pounds a quarter. With Richard Krygier as the formal publisher, McAuley set to work.

The first issue appeared some eight months later. It was far more literary than some of McAuley's polemics had suggested it might be. He would not allow Quadrant, he had announced, "to exemplify that ideal of a completely colourless, odourless, tasteless, inert and neutral mind on all fundamental issues which some people mistake for liberalism." The first issue had poems by Rosemary Dobson, Judith Wright. A.D.Hope, Vincent Buckley and Roland Robinson. (They all were metrical and rhymed.) There were articles by Hope, Alan Villiers, George Molnar, and George Kardoss. There were reviews of Patrick White, David Campbell and Judith Wright. The pages themselves were narrow and elegantly designed (by Henry Mund). Even the violet rejection slips had a hint of aestheticism.

Politically McAuley's first editorial referred to the recent Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution : "Suddenly this one huge glaring visage, this enormous mask made of blood and lies, starts up above the horizon and dominates the landscape. A figure of judgment speaking to each person in a different tone or tongue: And what do you think about me?"

He also touched on the crisis of modernity -- in the arts, sciences and society. He concluded with the famous lines : "Truly an exhilarating time! On condition that we have relevant principles worth living and dying for, and are not unnerved by the lightnings and thunders, the whispers and temptations, the beatings and the brainwashings...or by the rustle of dead leaves."

The critics welcomed the first issue -- except Max Harris who, then still smarting from Ern Malley, dismissed it as "arrogant and intolerant." But what else, he asked, would you expect from a Catholic? (He later became a valued contributor.)

Subsequent issues maintained the balance of the first -- of poetry, criticism and commentary. Culturally it continued to promote the arts of "beauty, use and meaning." Politically it sought to engage with the non-communist left. ("The editor," McAuley wrote, "has always regarded himself as inclining to the radical and libertarian side.") It welcomed articles from ex-communists (Alan Barcan, J.E.Henry, J.Normington Rawling) as well as left liberals (John Douglas Pringle) and conservatives (M.H.Ellis). [As for financial matters -- advertising, subsidies, donations, sales-- let me refer to my The Heart of James McAuley].

McAuley's Quadrant was undoubtedly a success when judged by the poetry and criticism it published, the debates it hosted, and the prestige it enjoyed. As the American poet and historian Robert Conquest put it: "Quadrant has survived and flourished in a jungle full of pygmies with poisoned arrows. Australia is lucky to have it and so are we in the world at large." For its part the Australian Committee for Cultural Freedom was more than satisfied.

So was McAuley at first. Yet, as his annual reports document, he grew increasingly dissatisfied. He had quickly given up a number of his early editorial ideas. He soon lost that bee in his bonnet about making Quadrant "Australasian", a sort of Australian-New Zealand forum. He also gave up his total opposition to reprints, welcoming some from Asian writers. His hopes for a lively letters-to-the-editor section did not work out in what was still a quarterly. He began to feel that his own editorial comments were too oppressively present. More importantly he was never satisfied that all of the articles on political and ideological themes had reached the level of literature that he aimed at, although many did.

There were also large changes in the wider world which were reducing the relevance of some Quadrant causes. In literature the era of "offensively Australian" nationalism and tediously dun naturalism was over. In politics the Communist Party had at last lost its allure following the suppression of the Hungarian Revolution. At the same time Ern Malley had shyly resumed publishing poetry and the non-communist left showed no sign of finding a way out of no-man's land. A New Left and counter-culture were emerging. The agenda of Volume I Number I needed revision.

But there was more to it still . McAuley was well aware that, as a poet he had exhausted his bardic, discursive and epic impulses with the completion of Captain Quiros. Had he also exhausted his editorial impulse with the creation and success of Quadrant which also belonged to those years on the high road of the exhilarating 1950s? The turn into the 1960s brought not quite a dark night of the soul, but a need for retreat and reconsideration, for the resumption of the lyric mode, a release of what Henry Kendall called "the soft surprises of the sun".

The issue was resolved in 1961 when, after six years with Quadrant, McAuley was appointed Reader in Poetry in the University of Tasmania. The move to Hobart was a major step. It reduced his deep involvement in "the New Guinea enterprise" and in the exhausting political-ecclesiastical warfare of Sydney. But it was also the end of a chapter in the history of Quadrant.

It was to some extent a welcome turn of events. By now McAuley was convinced it was time to pass the editorship to others. He remained an advisory co-editor and most definitely poetry editor. He became a regular, perhaps the most frequent contributor. He rallied to it in any crisis, cultural, political, financial. (It published the last poem he wrote before his death -- as a holograph in his italic script.) But the main editorial responsibility was no longer his.

Yet what a bequest he had left! Australians know that our poor country and culture have few authentic treasures. But those first 20 issues, McAuley's Quadrant, with their vibrant poetry, liberal faith and elegant design are one of them.

This paper was given at the recent James McAuley Conference at Sydney University. 2002

Peter Coleman

James McAuley's 20 Quadrants

Peter Coleman

to the rathouse

the Revivalist